Juliana S. Baggio and Natalia A. Peres, UF/IFAS-Gulf Coast Research and Education Center

If you grow strawberry or are somehow related to the strawberry industry, you must have heard about a new emerging disease, Pestalotia leaf spot and fruit rot, caused by the fungus Neopestalotiopsis sp. The taxonomy of this pathogen is confusing because it has gone through multiple reclassifications over the years, and it requires genetic (DNA) characterization. Researchers in Florida and Israel first reported a strawberry fruit rot caused by Pestalotia longisetula, subsequently reclassified as Pestalotiopsis longisetula. According to recent studies, isolates previously reported as Pestalotiopsis longisetula should be identified as Neopestalotiopsis rosae. This fungus has always been considered a weak or secondary pathogen and was most commonly found causing symptoms on roots and crowns during plant establishment. In some cases, it was isolated along with other root pathogens, such as Colletotrichum acutatum, and crown rot pathogens, such as Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Phytophthora spp., and Macrophomina phaseolina. Thus, it was never a major concern in the strawberry industry, until recently.

Pesaoltia leaf spot and fruit rot outbreak in Florida strawberry fields.

Strawberry Pathology Lab at UF/IFAS GCREC

Three years ago, a severe outbreak was reported in a single commercial field in Florida and, for the first time in the U.S., massive spotting symptoms were observed on leaves and fruit (Fig. 1). During the subsequent seasons, the number of commercial farms reporting problems with this disease has increased. Yield was severely affected, and in many cases, entire fields were rendered uneconomical to harvest and were destroyed. The common linkage among the initial outbreaks was the nursery sources from which transplants originated. However, the pathogen spread very quickly to other fields, particularly after rain storms. Studies performed by researchers at the University of Florida IFAS-Gulf Coast Research and Education Center (GCREC) confirmed that this is a more aggressive form of this fungus that may belong to a new Neopestalotiopsis species. Although leaf spots and fruit rots can also be caused by Neopestalotiopsis rosae, most isolates recovered during the recent outbreaks belong to this new species. Thus, isolates must be correctly identified before panicking! Currently, the pathogen can be found in most fields in Florida, and it has been confirmed in some farms in North Carolina, Georgia, Texas, Indiana, and Pennsylvania. For the rapid and accurate differentiation of Neopestalotiopsis species, the Strawberry Pathology Lab group at UF/IFAS GCREC has developed a molecular diagnostic tool (HRM) that is already being employed at the GCREC plant diagnostic clinic.

Management of this disease depends on understanding the pathogen’s biology and epidemiology and using integrated control approaches. Therefore, the Strawberry Pathology Lab at the UF/IFAS GCREC is currently working on several trials trying to answer growers’ most frequently asked questions.

Where did it come from? How does it spread?

Isolates from the ‘old’ Neopestalotiopsis population (a.k.a. Neopestalotiopsis rosae) and from the new population were selected for complete genome sequencing. Comparative genomic analysis to identify genetic clues to the recent outbreaks are currently being performed. Results are expected to generate insights into the origin and aggressiveness of the emerging population.

Since the disease was observed in fields where it was observed the previous season, field surveys in strawberry nursery and fruit production fields were conducted, and Neopestalotiopsis was able to be recoved from soil, crop residue, some asymptomatic weeds, and a few alternative hosts around strawberry fields. However, many other Neopestalotiopsis species found on those other hosts were not the new aggressive strawberry species and do not cause disease on strawberry. It is hypothesized that crop residue within strawberry fields serves as the main source of inoculum for disease outbreaks during the following season. However, more studies need to be performed to clarify this hypothesis and to provide a greater understanding of the pathogen’s ability to survive under different conditions and the main factors influencing disease spread within strawberry fields.

Within the season, Neopestalotiopsis is easily spread in the fields by wind, water (overhead irrigation and rain), farm equipment, and field workers during harvesting and cleaning operations. The most favorable temperature for disease development is 68°F (20°C); however, disease symptoms can be observed even at 41°F (5°C) after 48 hours of leaf wetness (water on the surface of the leaves). It seems that leaf wetness, plays a more important role in pathogen infection and disease development than temperature.

How can it be managed?

Researchers in the UF/IFAS Strawberry Pathology Lab have been testing different management approaches to control this disease. When possible, acquiring disease-free transplants is the first step to avoid the introduction of the pathogen in a field and escape or delay the occurrence of the disease. However, symptoms are not always easily recognized and can be confused with other leaf spot diseases of strawberry (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/PP359). Thus, routine inspections and sample submissions to a diagnostic clinic for accurate identification are crucial.

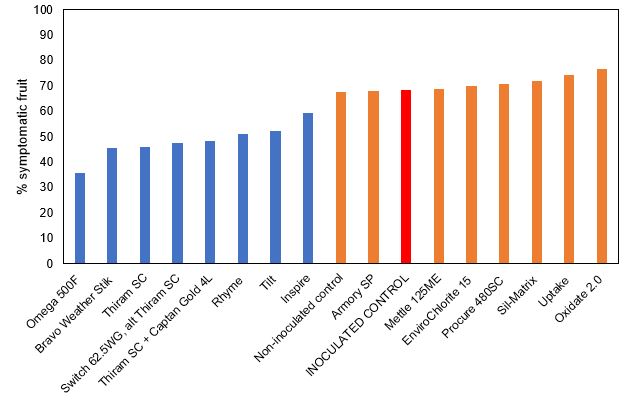

Limiting field operations, such as harvesting and spraying, when plants are wet is important to minimize spread within and between fields. Dispersal can be minimized by hand sanitation, cleaning and disinfestation of equipment, and performing farm operations in affected fields when plants are dry. The efficacy of fungicides in controlling Neopestalotiopsis has been tested in laboratory and field experiments. Products with the most promising results in the laboratory were selected for evaluation in field trials. During the 2020-21 Florida strawberry season, Omega 500F, Bravo Weather Stik, Thiram SC, Switch 62.5WG rotated with Thiram SC, Thiram SC + Captan Gold 4L, Rhyme, Tilt, and Inspire reduced fruit disease compared to the non-treated, inoculated control (Fig. 2). These same treatments also increased yield over the non-treated control. Omega 500F and Bravo Weather Stik are not registered for strawberry production fields but could be considered for strawberry nursery production (Omega is in the process of registration for nursery use). Unfortunately, our industry already relies greatly on Switch for control of Botrytis fruit rot (BFR). The overuse of this product can lead to increased selection for fungicide resistance; thus, applications need to be limited to the maximum recommended on the label, and the need to continue seeking alternatives persists.

As part of the integrated management program for this disease, the Strawberry Pathology Lab team has been collaborating with the Strawberry Breeding Lab at UF/GCREC to investigate potential sources of resistance in commercial and wild strawberry. Screening for host plant resistance is valuable in case the disease cannot be contained, and strawberry nurseries and fruit growers will need to manage the problem every season. All of the Florida cultivars evaluated were susceptible to the disease. The commercial cultivars Florida Beauty and Florida Brilliance were significantly more affected than SensationTM ‘Florida127’, ‘Florida Radiance’, and the new ‘Florida Medallion’, which showed intermediate susceptibility to the disease. Older cultivars such as Strawberry Festival and Treasure and the new white cultivar Florida Pearl were less susceptible, but none were found to be completely resistant.

Other trials testing the efficacy of fumigants in reducing Neopestalotiopsis inoculum in the soil and crop debris at the UF/IFAS GCREC facility and commercial production fields during the 2021-22 strawberry season are on-going.

This new disease is difficult to control, and the UF/IFAS strawberry researchers are working hard to develop an integrated disease management approach involving the needs of the strawberry nursery and production industries. For more information on this disease, please see the UF/IFAS EDIS publication at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/PP357 and do not hesitate to contact Juliana Baggio, jbaggio@ufl.edu, or Natalia Peres, nperes@ufl.edu.