Rebecca A. Melanson, Extension Plant Pathologist, Mississippi State University, and Aaron Cato, IPM Specialist, University of Arkansas

Diagnosis is the first step in pest management. It is first necessary to know the cause of a problem before appropriate management methods can be implemented. Management methods that do not accurately address the problem at hand can add to production costs and delay implementation of effective management methods, which can lead to an increase in yield losses due to the ongoing problem. Oftentimes, physical samples are submitted for disease or insect diagnosis. However, in the digital age of smartphones and email, county agents, diagnosticians, and Extension specialists increasingly receive emails and/or texts with digital images (photos) of plants or insects asking for assistance in identification and management. Travel and other restrictions brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic have further popularized the use of virtual diagnostics. In some cases, such requests are made through an online system used by the state university diagnostic laboratory or clinic. While digital images can be informative, it is not always possible to diagnose a problem from images alone. This is particularly true with plant diseases as many produce symptoms that are similar and cannot be distinguished without examination of a physical sample. In addition, it is sometimes necessary to to isolate a pathogen or perform laboratory tests to detect and identify a pathogen present in a sample.

The following tips and guidelines for taking digital images and getting assistance with digital diagnostics are intended to help you make the most of your efforts and help us better serve you:

Get to know your local county agents and specialists and become familiar with the capabilities and guidelines of your local state university diagnostic facilities! This will allow you to act quickly when time is of the essence. University diagnostic facility websites: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, South Carolina, Virginia

Provide relevant information with submitted images. This includes the date the image was taken, the date symptoms first appeared, information about the crop in question (host/species, cultivar/variety, plant age, etc.), the crop stage, field distribution, field history, and any other relevant events, such as recent weather conditions prior to symptom development or pesticide applications that recently occurred in the affected planting. Information such as planting location (field or enclosed structure), production type (commercial vs. home garden), and pesticide usage preferences (conventional vs organic) can also help when developing management recommendations. When sending images, it is also a good idea to describe the observed symptoms and how they may have changed over time. Much of this information is requested on the sample submission forms for the various university diagnostic labs (examples: Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, South Carolina, Virginia).

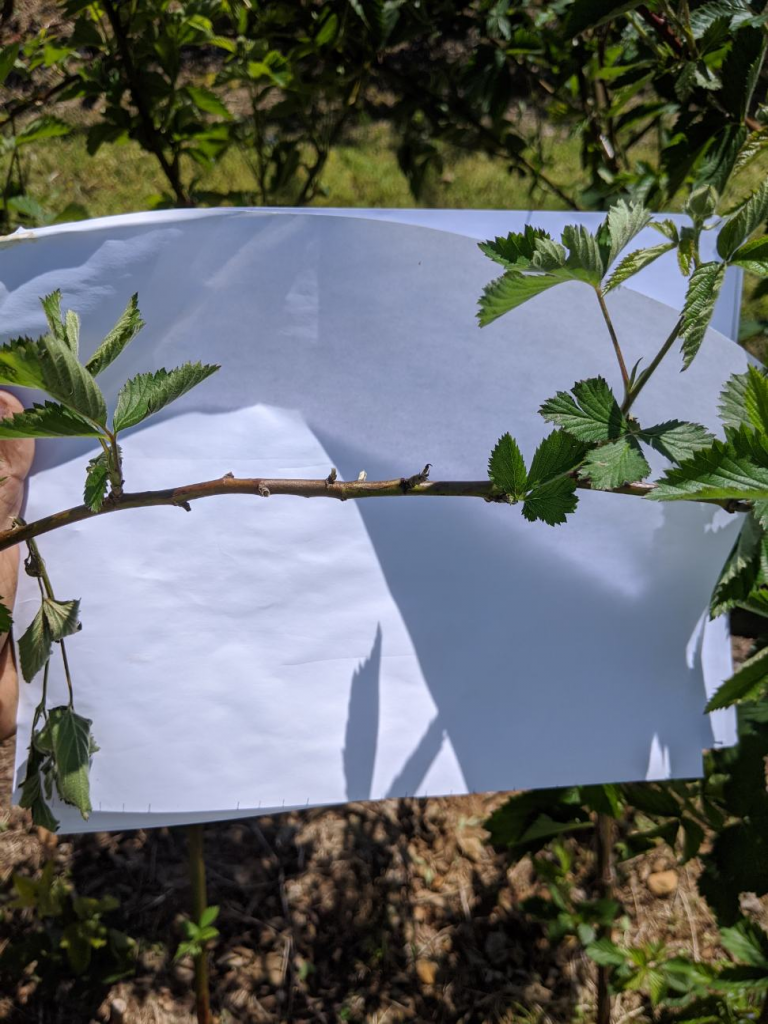

Make sure images focus on the correct target. Clear images can be hard to take within a crop canopy where there are many focal points. Be sure to center the photo on the symptom or insect in question, adjust the focus, and take multiple photos. It may help to use a sheet of white paper to provide a solid background to help with focusing images (Photo 1). Images should be reviewed and checked for clarity before submission.

Take multiple high-quality photos that capture the various symptoms and different views of the affected plant. Depending on the cause of the problems, symptoms may be present on multiple plant tissues or may occur on particular areas of a plant (upper or lower leaves) or in certain patterns in a field (random or clustered). Taking images that show each of the different symptoms on various plant tissues, the entire plant (a “plant view”), and the landscape where the symptomatic plants occur (a “field view”) can provide relevant information to assist in diagnosis. Examples and explanations of these situations are provided in Photos 2, 3 and 4.

When sending photos of insects, if possible, include images of the suspected damage or the plant part that was being fed upon. Insect pest diagnosis in specific crops can often be achieved with damage symptomology alone (Photo 5), and many times the insect pictured is not related to specific damage symptomology (Photo 6).

Hint: Taking clear photos of live insects can be incredibly difficult if they are actively moving. Capture insects and place them in a freezer for 10-20 minutes. This will slow the insects down and allow for a clear and focused image.

Include something of known size in the image. This can often be achieved by including plant parts with photos of insects. However, zoomed in images of disease symptomology or insects can be hard to discern. Consider including a ruler or coin or other small item of known size in the image when possible (Photo 7).

More information and examples of images for plant disease assistance are available in the MSU Extension factsheet “Taking Photos of Plant Disease Problems.”