Dr. Jackie Lee, University of Arkansas, Fruit Research Station Director

My first research project was funded through IR-4 and entailed finding management options for raspberry crown borer (RCB). I began that work in 2003 at the University of Arkansas Fruit Research Station as an MS student, under the direction of my advisor Dr. Donn Johnson, who retired recently and was also instrumental in these recommendations and research. In 2019, I took the role of Director at the University of Arkansas Fruit Research Station so I am sitting at my desk 18 years later writing this article from where it all began, which brings back a lot of good memories and hard work! There is a reason why RCB was not well studied, since it entailed working in thorny blackberries, digging blackberry plants, and cutting every inch of them by quarter inch pieces with hand pruners. Glad we have mostly thornless varieties on the station nowadays! It was all worth it in the end because we were successful in pinpointing important life history characteristics of RCB that were monumental in learning how to effectively manage it. We were also able to provide data to support adding chemicals to our toolbox. A few new chemicals have been added since then but for the most part recommendations have not changed much since I published my work in 2005.

Raspberry crown borer, Pennisetia marginata, is a diurnal moth that flies during the day and mimics a wasp (Figure 1). They are so convincing that to the untrained eye they are mistaken for a common yellow jacket. These cryptic insects are devastating to blackberry and raspberry plantings. The larvae tunnel into canes and the crown of the plant to feed. This reduces yield, kills canes, reduces plant vigor and ultimately can kill the plant.

Figure 1. Photos courtesy Dr. Donn Johnson, University of Arkansas emeritus.

The adults emerge from the crown of plants in mid-September, take flight, mate, and lay eggs on the undersides of blackberry leaves. During this time, you can estimate your current infestation by examining the crowns for exit holes that contain a protruding pupal skin (Figure 2) or look for the eggs on the underside of leaves around the margin (Figure 3). You can also examine spent floricanes this time of year. If you notice many are hollow, could be RCB. A good sign to look for in spring and harvest season is a shepherd’s hook appearance at the tip of floricanes (Figure 4). This is due to the larva feeding up into the pith/middle of the cane and shutting off nutrient and water flow to the tip of the cane, which causes it to wilt. This will cause the floricane to produce less fruit, no fruit, or even die back. If you find a lot of floricanes that are hollow after harvest season during pruning, then you likely have an infestation.

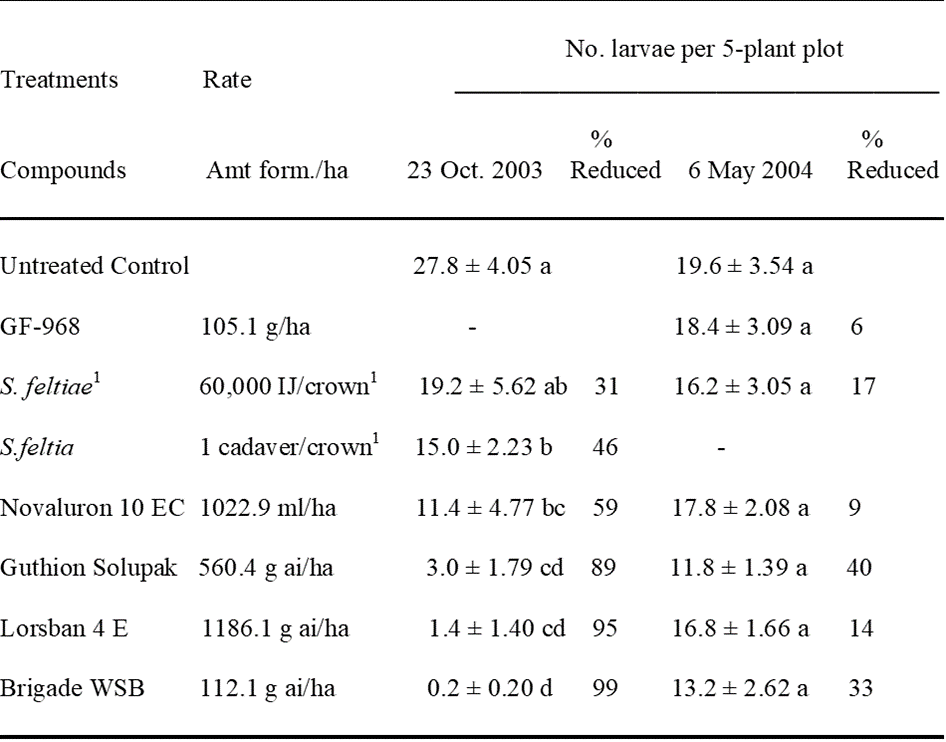

If you identify that you indeed have RCB then treatment is advised. There is not a derived threshold and I recommend treatment if any are discovered. The timing of treatment is critical due to the life history. I spent hours observing RCB in the field and the lab. Adult emergence and egg lay occurs in September in Arkansas and likely similar timing for much of the southeast. Emergence could be earlier in more southern locations. Once the larvae hatch in early to mid- October, larvae will crawl down the canes, or fall to the ground on a silken thread and make their way to the crown of the plant or first 2-4 inches of the cane. They burrow into the crown/canes and overwinter in the cambium just under the bark usually in a crevice, in October/November. They will overwinter and feed here under the cambium for a short time of their life cycle. In spring, they will bore in deeper and begin feeding on the pith of the plant (Figure 5). It is critical to apply pesticides before this time. Once they bore into the plant, they become more difficult, almost impossible to control. Early spring is often advised as a good spray timing but the efficacy drops by 2/3 per my research, utilizing bifenthrin (Table 1). The best timing for chemical management we found is mid-late October.

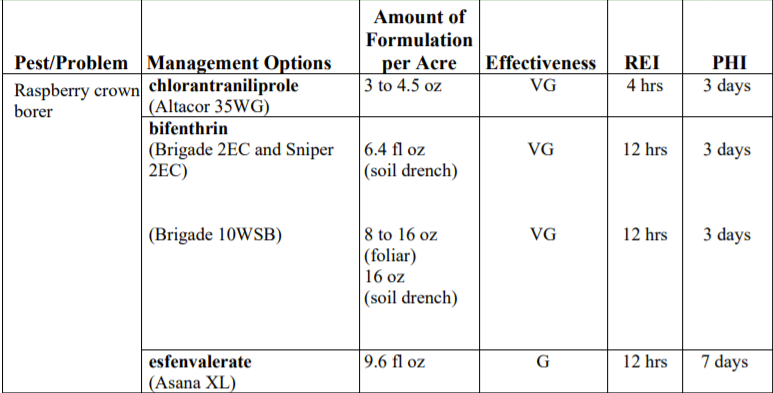

I recommend using flood nozzles to deliver a soil application but make sure to direct the spray to include the bottom 2-4 inches of the canes. I also recommend 50 gallons of water per acre. We compared multiple rates of water to deliver chemical and found that 50 gallons of water per acre was comparable in efficacy to 100 gallons for RCB. As for chemicals to use, there are not many options. When I first started this research in 2003, guthion was the only labeled chemical but was soon removed for use. We were able to get an RCB crown drench added to the bifenthrin label in 2005. Esfenvalerate and chlorantraniliprole were also labeled long after this research and have proven to also offer good control in more recent studies. We looked at nematodes as well for control and found them inferior to chemical management but they did offer 31-46% reduction in RCB larvae. I know these data are old but they still tell a powerful story on how timing is critical for RCB control and that an early spring timing may be too late (Table 1). It also shows how effective bifenthrin can be as a management tool.

Table 1. Please note the only currently labeled chemical for use against RCB in this table is bifenthrin (Brigade WSB). Other chemicals used were for research purposes only. This table depicts chemical applications for raspberry crown borer in blackberry plots at two different timings, October and May. Reduction of larvae is given as a percent. ALL fall applications were superior. Brigade WSB (bifenthrin) provided excellent control.

Summary

How to identify RCB infestation.

- Shepherds hook at the top of floricanes during early spring and harvest season

- Dieback of canes that resembles winter injury during season

- Exit holes at the base of the plant with a pupal skin protruding in early fall

- Brown eggs on undersides of leaves

- Hollow floricanes at the end of harvest season

- Low plant vigor

- Cut into canes and crowns of low vigor plants to look for larvae*

* If you notice cane dieback, low plant vigor, or a shepherd’s hook, investigate further and cut through the cane in question to see if it is hollow. If it is hollow, cut it lengthwise and split it down the middle to expose the larvae. They tunnel from the crown, up the canes.

How to treat an RCB infestation.

- Make chemical applications in the fall.

- Apply a registered pesticide with flood nozzles delivered in at least 50 gallons of water per acre. Make sure to direct at the bottom of the canes as well.

- Rogueing may be used as a cultural control method by removing any infested canes before adult emergence and burning them. Some larvae only feed in the crown so this method may not be highly effective unless the entire plant is removed.

Table 2. Current labeled chemicals. Please note to check your state registry and read the pesticide label. Approved chemicals can vary from state to state and pesticide labels can change quickly.